Right around the start of November, two words suddenly disappeared from the chatter in the bond market: debt supply. As bond prices surged across the developed world day after day, sending yields tumbling and handing investors some much-needed profits, the angst about soaring budget deficits melted away.

But for how long?

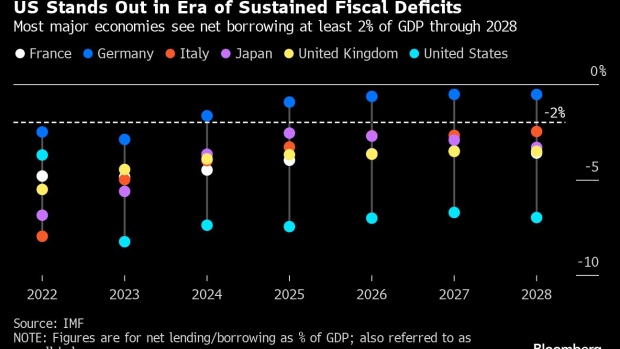

Over the next several weeks, governments from the US, UK and the eurozone will start flooding the market with bonds at a clip rarely seen before. Saddled with the kind of bloated deficits that were once unthinkable, these countries — along with Japan — will sell a net $2.1 trillion of new bonds to finance their 2024 spending plans, a 7% increase from last year, according to estimates from Bloomberg Intelligence.

With most central banks no longer hoovering up bonds to bolster economic growth, governments must now entice more buy orders out of investors around the world. To do so, the thinking goes, they will have to dangle higher yields, just as they did when concern about ballooning government debt loads was amplified this summer by Fitch Ratings’ move to strip the US of its AAA credit rating. The rout that resulted sent the rate on benchmark 10-year Treasuries above 5% for the first time in 16 years.

Those jitters may have faded of late — primarily because slowing inflation prompted investors to suddenly fixate on the idea that central banks will start cutting interest rates — but many bond-market analysts argue that, given the current supply-and-demand dynamics, it’s only a matter of time before the nervous chatter picks up. Indeed, bond yields have already lurched higher this year.

“Right now, the market is just obsessed with the Fed rate cycle,” says Padhraic Garvey, head of global debt and rates strategy at ING Financial Markets. “Once the novelty of that fades away, we’ll start to worry more about the deficit.”

Will aging society increase or decrease global demand for bonds? Share your views in the latest MLIV Pulse survey.

It’s hard to know exactly how much these soaring debt loads drive up borrowing costs. Researchers at the Bank of England and Harvard University took a stab at it a few years ago. Their joint study concluded that each percentage-point increase in a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio pushes up market rates by 0.35 percentage point.

The math certainly hasn’t worked out that way in recent years. (Treasury yields, for instance, have fallen this century as US debt-to-GDP spiraled higher.)

Imperfections and all, Garvey says the study’s findings should be heeded. With the US now running annual deficits equal to 6 percent of GDP, about double the historical norm, he figures that’ll tack another percentage point onto yields. Not only would that swell the government’s interest tab and deepen the deficit further, creating a vicious cycle of sorts, but it would drive up borrowing costs for companies and consumers and curb economic growth.

Public finances aren’t quite as bleak elsewhere but countries including the UK, Italy and France are all expected to post larger-than-normal deficits again this year. And a plethora of elections will keep those shortfalls in focus; BlackRock Inc. this week warned that Britain’s politicians could spark a selloff in the nation’s bonds if they try to win votes by pledging greater spending.

“It’s difficult,” Garvey says, “to argue that this is inconsequential.”

And yet bond bulls essentially do just that. Steven Major, the head of global fixed-income research at HSBC Holdings, is the loudest of those in this camp. He admits the magnitude of the Treasuries rout that followed the Fitch downgrade took him by surprise, but the episode, which saw the 10-year yield spike 1 percentage point over the course of a couple months, did little to change his view.

Major likes to use an analogy about farmers selling potatoes in a village whenever he’s asked about debt supply concerns. He asserts that an increase in supply, whether it be of potatoes or bunds, doesn’t necessarily have to trigger a drop in the price.

That’s because the demand side of the equation is unknown, he says. There could be more buyers about to show up from the village down the road or from sovereign wealth funds in the Middle East. And in times of recession, which is when deficits become most acute, demand for the safety of government debt tends to pick up.

“It’s wrong to assume if you increase the supply of something, the price has to go down,” Major says.

He also argues that if demand for bonds isn’t keeping up with the increase in supply, governments can simply scale back the sale of longer-term securities and offer more shorter-term debt.

This is exactly what the US did when the sell-off got ugly last year. In early November, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen slowed the increase in sales of 10-year and 30-year bonds, and opted to issue more T-bills than the market expected. The move, while not without its own set of risks, helped settle jittery investors and laid the groundwork for a bond rebound.

Read More: US Slows Its Ramp-Up of Longer-Term Debt Sales, Spurring Rally

Analysts at JPMorgan Chase expect the Treasury to use the T-bill market for a smaller proportion of its funding in 2024. They estimate $675 million of net T-bill sales, roughly a third of last year’s tally, but a figure that nonetheless comes on top of the forecast bump in note and bond sales.

“The Treasury has shown us that they are going to try to be pragmatic about where they issue on the curve and when,” said Rebecca Patterson, formerly chief investment strategist at Bridgewater Associates from 2020 to 2022, and an early proponent of the case for higher yields. “That’s reassuring at the margin but it doesn’t change the bigger picture. The supply of debt we need to issue to fund the government spending and to fund the deficit absolutely is an ingredient in where bond yields settle.”

It’s also a driving force in how investors decide which bonds they want to own. So far, one of the big trades for 2024 is a bet that US debt with a lifespan of 10 years or more will return less than shorter-term securities, because longer-dated bonds are more sensitive to worries over the deficit.

As much as fiscal spending has surged in the US and Europe in recent years, Alex Brazier, the deputy head of BlackRock’s research arm, sees two bigger problems pushing up debt loads and wreaking havoc on the market: slowing global growth and higher benchmark interest rates.

The European Central Bank has pushed its main rate above 4% to tame the inflation surge that was triggered in part by the pandemic stimulus programs. The Bank of England and Fed have gone even higher — to over 5%. Even if they start reversing those hikes next year, as is now expected, there’s little chance of a return to anything resembling the zero-rates era that prevailed for much of the previous two decades.

This means “you can’t grow your way out of debt so much and the interest bill is bigger,” Brazier says.

In France, the finance ministry is grappling with interest payments that are forecast to exceed the nation’s defense budget this year and are set to almost double by 2027. And Australia’s government is squirreling away cash to meet its spiraling debt obligations, which will soar to a record by mid-2026.

The World Bank said in March that potential global growth, defined as the highest long-term rate at which the economy can grow without triggering inflation, is set to fall to just 2.2% a year through 2030. That’s its lowest level in three decades as investment, trade and productivity, the three forces that usually power economic expansions, all slow.

“It’s the poor macro environment,” Brazier says, “and that makes the fiscal deficit an issue.”

His recommendation to clients is simple: Stay away from long-term bonds.

Source: norvanreports.com